When my dad bought the first sheep for our farm several years ago, we had no idea what we were doing. You can’t, after all, coming from a city background with no experience with animals whatsoever (besides a lapdog and a house cat), let alone experience with sheep. We had just built our barn, and were excited to get animals to fill the stall room. So, we got a couple of Toggenburg goats, as well as three Dorset cross ewes.

We bred the ewes in October, because that’s what everyone said to do, and were greeted in March with a few sets of lambs. However, the sheep couldn’t “quite” do it, and the veterinarian was called out to assist in the birth of the lambs. We fed the sheep hay and grain, ‘cause that’s what everyone said to do, and in the summer we let them graze in a paddock in our orchard. Summer came and went, and in October we again bred the sheep. The vet was again needed in March to assist. That was the year we discovered Rotational Grazing, moving the sheep to a new paddock of grass every so often, giving the old paddock some time to recover before being grazed again. So, we divided our orchard into four paddocks, giving the sheep one week to graze each one. By the time paddock #4 had been grazed down, paddock #1 (supposedly) had enough grass to be grazed again.

When July came, the sheep needed to be sheared. We had had a negative experience with this job the previous year, having to emergency shear the sheep ourselves with a cheap pair of hand shears hastily ordered from Amazon during a heat spell, since the sheep-shearer wasn’t able to come until the following month. Because of this and a few other factors, we eventually got rid of those sheep and found Katahdins, another breed of sheep. Katahdins are known for their hardiness, parasite resistance, and good maternal traits/mothering instincts. Katahdins are also a hair sheep, which basically means that they shed their wool instead of needing to be sheared. In 2020, we got four yearling Katahdin ewes. Since then, we have stayed with Katahdins, impressed with their overall hardiness and maternal traits.

We bred the ewes in October, but, when 9 lambs and 5 goat kids were born on the coldest week of March, we began to question this method of breeding and lambing. It didn’t seem like, in nature, the deer were born in cold, snowy weather, confined in 5′ x 5′ lambing jugs with heat lamps, bucket heaters, and grain rations, like our sheep were. But, up to this point, that’s all we had ever done – what everyone had to told us to do.

So, eventually, we began breeding our ewes in December and lambing on pasture in May. We also stopped feeding grain, raising our sheep solely on grass, and hay in the winter. With the help of Peter Burkel, who I wrote about in my last blog Picking Up The Sheep, we converted our 3 1/2 acre hayfield into a pasture, and began practicing Management Intensive Rotational Grazing.

Grazing

How Management Intensive Rotational Grazing, or MIRG, for short, differs from Traditional Rotational Grazing is in theory, quite similar, but in reality quite different. Instead of rotating the sheep onto a new Paddock every 1-2 weeks, the sheep are moved every 24 to 48 hours. There are a few reasons for doing this: when you compare sheep to a patch of grass, you must compare them with children and a candy store. When the sheep are moved onto a new paddock, they will all rush to their favorites- the “candy”. Whatever grasses these are, they will be mowed down first. In a large paddock, over multiple days, the sheep will eat only their favorites. When the mowed down “candy” tries to regrow, the sheep come and eat it up again. This leaves an uneven paddock, with bare spots mowed down to the dirt, the “candy”, and other untouched spots, the “vegetables”. We began to find this out in our old method of grazing when, over time, the pasture couldn’t keep up with the sheep the same way it had only a couple years before. Now, using MIRG, after the sheep have grazed one paddock adequately for 24 hours, they are moved onto the next paddock – with no access to the previous one. With less to graze in a one-day paddock (much smaller than a one-week paddock) the sheep eat everything – “candy” or “vegetables”. By the time the sheep are back on that same paddock, it has had 40 to 50 days to regrow, plenty of time to recover, ready to be grazed again.

Another reason for this form of grazing is protection from parasites. I wrote about this briefly in my first blog, Ivar’s Workshop. Parasites live in sheep, like anything else, but sheep are much more susceptible to parasite overload than other animals. The eggs take 3 to 14 days to hatch once they’ve come out of the sheep’s feces. The sheep ingest the parasites by grazing the infected grass lower than 6 inches. However, this is not a big problem in Management Intensive Rotational Grazing, because by the time the eggs have hatched, the sheep are already at least three paddocks away. The parasites eventually die off, not having an animal to live in. The sheep will not return to that paddock for another 40-50 days depending on however many paddocks there are, plenty of time for the paddocks to regrow, ready to take another grazing.

Selecting & Culling

Sometimes, however, parasite problems and other problems cannot be avoided with certain sheep. This is where you have to set your boundaries, and whatever sheep fall outside of those boundaries have to go. I have chosen not to use dewormers or other medicines with my sheep, with the intent of creating hardy sheep that do not need medicine or dewormers. This means, however, that I have to be a lot more vigorous in my culling, getting rid of disease or worm prone sheep.

I remember one time when we had our sheep grazing in our woods for two weeks. One night, we noticed that two of our sheep, a set of twins that had been born four months earlier, were missing. After 10 minutes of searching the woods, we found both lambs dead with potbelly, an internal parasite disease. The next day the lambs’ mother died. Now, this situation maybe could have been prevented, we just didn’t know any better at the time. But, it goes to show that one ewe and both her lambs couldn’t hold up to the parasites that the other sheep could. Preventable or not, I don’t want those genetics in my flock.

Another good reason to for me to cull a sheep is because of bad mothering instincts. When the first four Katahdin ewes that we got lambed, we culled two of them because of bad maternal traits, such as lamb rejection and deformed teats.

Another reason to cull sheep is because they are fence jumpers. When you rotationally graze with Polywire like me, you try to make as many improvements as possible to make your every day easier. One of these “shortcuts” is a “short fence”. In other words, instead of moving a three-wire fence every day, it is much easier to move a one-wire fence for times’ sake. This is what grazers like Greg Judy and Peter Burkel do, using one electrified line 18 inches off the ground to hold in both cattle and sheep. One wire at 18 inches obviously can’t physically hold in a sheep, since they can just hop over it, so you have to train them, starting with three wires, then gradually down to two wires, until they respect that, and eventually one wire. Once you have gotten to this point, to have one sheep jump the fence can be extremely detrimental to the flock because it teaches the other sheep that this is an option. This is where culling comes in. One jump, and maybe two jumps may be pardoned, but three strikes and they’re out.

A friend of ours once said, “If a sheep can jump out of my fence, it can’t jump out of my freezer!” This may seem cruel or unfair, but just know that as soon as that jumper teaches the rest of the flock, you have to start all over again.

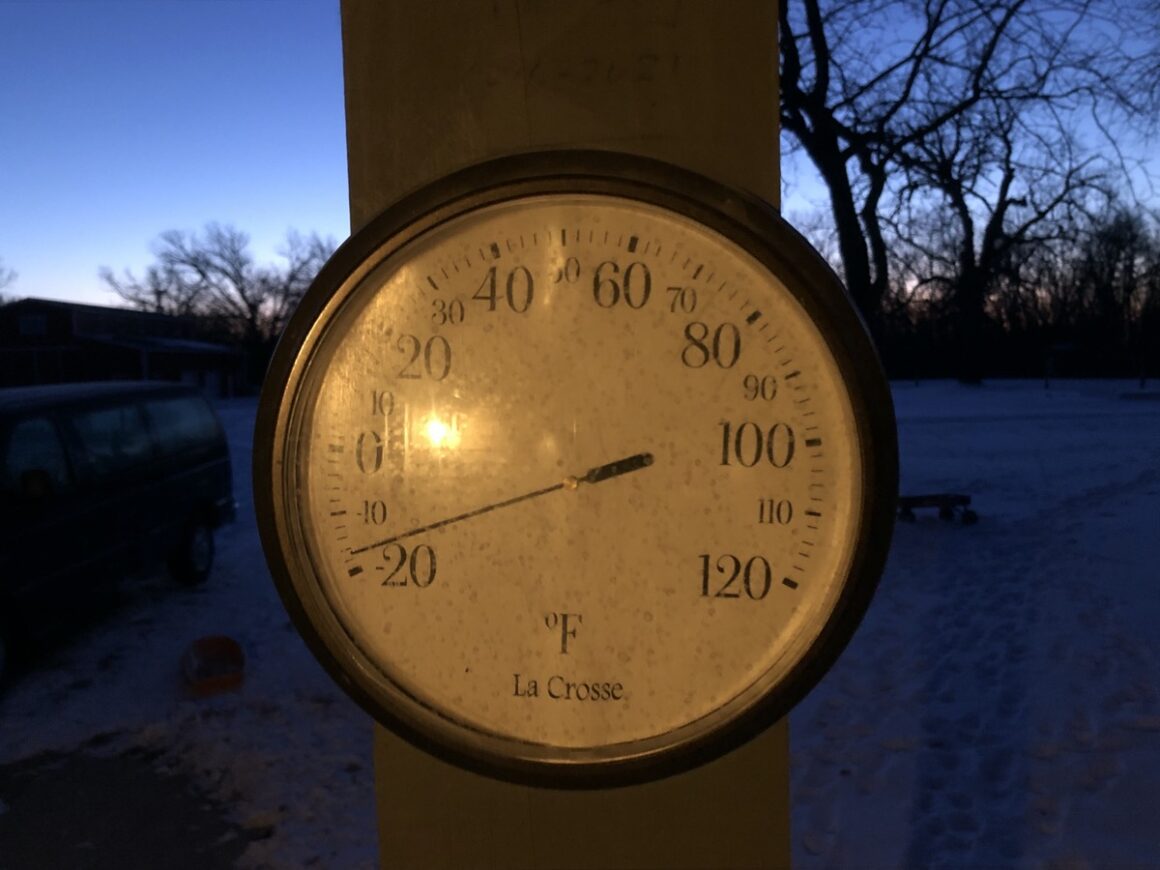

Other reasons to cull sheep from your flock include ewes that produce small lambs, and sheep that can’t stand up to cold weather. You can’t really know for the latter, but “nature takes care of itself”. I’m writing this in February and though I try not to hold to a formula, my sheep are out getting hay on pasture when it’s 0° and up, in our corral when it’s -1°F through -15°F, and in our barn when it’s colder. Last night my sheep were in the barn and it was -21° out. I let them out into the corral this morning with hay and access to our two-sided loafing shed, where they usually spend winter nights, when it was -11° out, but I know they’ll be fine, because they’re hardy sheep.

Management

In the summertime, as I have already stated, I Intensively Rotationally graze my sheep, moving them into new temporary paddocks every day. I use electric fencing and step-in posts to create my paddocks. I currently have six [hopefully] bred ewes, and two meat lambs to be butchered in a few weeks.

In the winter, my sheep go out to a fenced paddock that I set up at the beginning of the season, where they are fed hay I lay down on the frozen pasture. The seeds from the hay, mixed with the sheep’s manure, go down onto the dormant pasture, which helps that paddock immensely. The sheep lamb on pasture in May, and then are bred again in December.

So, that is how we got from those three Dorset ewes back in 2015, not knowing what we were doing, to where we are today. At fourteen I’m no expert, by any means, but feel privileged to get to share what I’ve learned through the past several years. Since we named this property: “The Grovestead – A Learning Farm” that has truly been our desire – to learn skills that have been lost, because we believe that they will be essential for the future. We’ve learned by doing, and that is truly the best teacher.

2 comments

ivar, I thoroughly enjoyed your account of learning how to become a master shepherd. I grew up on a farm where we raised 20-30 sheep for several years. I look forward to reading the Grovestead newsletter. It sounds like you’re also becoming a great wood craftsman.

Great story and information, Ivar. Thanks for sharing.