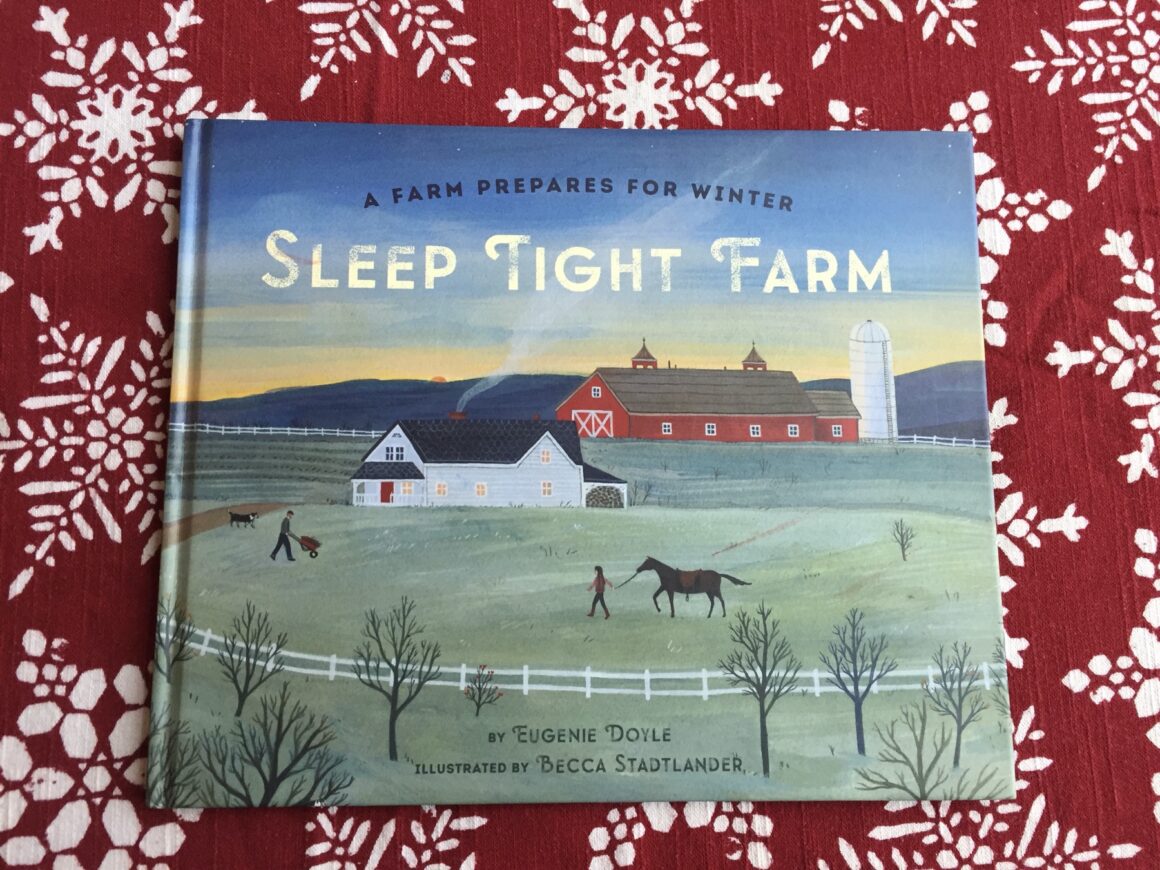

One of our favorite farm books is called Sleep Tight Farm. It talks about a family winding down their farm, getting it ready for winter.

It starts out, “The December days shorten and darken. We are busy putting the farm to bed…”

It’s a perfect description for what it’s like to get a farm ready for winter: “putting it to bed.” In the book, they talk about storing crops for winter, storing hay for the animals, splitting and stacking wood for the woodstove and sugar shack, and covering the beehives.

We like this book because, first of all, its beautiful—well written and beautifully illustrated. The words and imagery evoke a peaceful, quiet life. Food that is grown and harvested all spring and summer sustains life through the winter. Life which is resting and reflecting.

We also like the book because it reflects our own farm in so many ways. We have field crops, we make our own hay, we stack firewood to heat our house and evaporate maple syrup. We even have honeybees (on most years).

And just like the family in the book, we wind everything down for winter hibernation too. Reviewing our Farm Calendar, these are some of the ways we put our farm to bed each year:

Chickens

We keep both laying hens and broiler chickens. The broiler chickens come in the spring (about 60 of them) and do not make it to winter. But the laying hens get special treatment. We swap out their garden-hose drip-waterer with standard chicken waterers sitting atop a heated base (a homebrew project). We clean out the coop and put down fresh bedding. Finally, we hook up an extension cord which powers a timed lightbulb to keep egg production going (chickens do not lay in short daylight), as well as a heat lamp for extra cold days.

Sheep

We keep our grass-fed lamb until about October or November, when they are brought to the butcher. It takes a lot longer to raise sheep on pasture, but the quality and taste is far superior. The breeding ewes are very winter-hardy and can withstand extremely cold outdoor temps due to their heavy wool fleece. That said, we always offer them indoor accommodations in case they need a break from the wind.

Goats

Goats are almost as winter-hardy as sheep, but not quite. They spend the summer chowing on pasture and shrubs in our groves. When it gets cold I open the barn stalls and let them come in. We keep the barn doors open on all but the coldest winter days, so they are free to come and go as they please. But mostly, they prefer never to leave the cozy stable. We get out bucket heaters to keep the water thawed and heat lamps for very cold days.

Honeybees

Wintering bees is hard, which is why most people don’t do it. They usually ship their bees to Texas or California for the winter. We have never successfully overwintered a hive. They have either fled the hive come spring or they were not strong enough to make it that long. This has also been the case with other beekeepers I’ve talked to. I personally think that since all our colonies come from warmer climes (i.e., California) they are not acclimated to Minnesota winters. Clearly wild bees do survive Minnesota winters, otherwise we would never see them here. So I am planning to bait and capture a wild colony one of these years and see how that goes.

Fields

Our biggest summer task is storing up hay for the winter. We make three cuttings a year and get about 100 bales each cutting (easier said than done). Most of that is sold to other farmers, but depending on how many animals we are keeping overwinter, we hold back about 50 to 100 bales.

Gardens

As much of our garden that can be preserved is canned. This includes tomatoes, raspberries, strawberries, sweet corn. The blueberries are better frozen, but it is always with some sadness because nothing beats fresh-eaten. The potatoes, carrots, onions and garlic are stored in our basement. The potatoes and carrots in a makeshift root-cellar box that has to be moistened every so often. The onions and garlic are braided.

Firewood

We go through a lot of firewood every year. I don’t know the exact amount because we’ve never made it through a winter without running out (we have a furnace too). I think we would burn about 6 to 8 cords a year, which is a lot. In the fall we begin splitting and stacking firewood in our woodshed. Ivar and Elsie are old enough now to help with Dad’s supervision.

It’s all a lot of work, but there is a season for everything. Having just finished preparing the farm for winter, it is time for us to sleep tight. Now we rest, reflect, and in this season of Advent consider our Creator who resurrects new life each spring.